A portrait must be more than simply a likeness of the subject, it must convey personality and character. And beyond that it must be a work of art in its own right, fulfilling my belief that art is defined as the metaphors with which we share our unique experience with the world. The artist discovers the subject through the filters of his or her own life, to the point where the process of creation is a dialogue with the suibject. (Sal Mineo, oil, 16x12")

Thespianage - My Journeys In Art

An artist need never be bored. All it takes is a surface to work on and something with which to make marks. The blank paper or canvas beckons. I define Art as the metaphors with which we share our unique experience of life. Thespianage suggests to me the drama played out in the world around us in every moment, and the act of standing apart and recording what we see and feel in a way that paradoxically connects us to others.

Sunday, February 21, 2016

Friday, January 08, 2016

Say "Cheese"

Jack, oil, 8x6"

I’ve found that a major challenge facing me as a

portrait artist is a smiling subject. From a strictly technical point of view,

the complex musculature of the face creates a topography of hills and valleys,

peaks and crevices that render the expression difficult to capture believably.

It isn’t simply the mouth alone that is affected, the entire face is altered

significantly, creating a myriad of value changes that require careful

attention. Of considerably more concern, I believe, is what I’d

call the psychology of the smile. A spontaneous smile is a delight, but to hold

a pose smiling is deadly. Invariably the smile is not only forced, but

accomplishes exactly the opposite of what the portraitist is trying to capture.

It is a mask, that hides the true self of the subject. Few have risen to the

challenge better than Franz Hals. I credit his Laughing Boy as an inspiration.

Tuesday, December 01, 2015

Illustration and Narrative

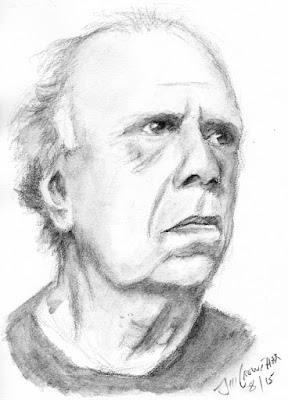

(Self-portrait, 8x6", water-soluble graphite)

As a Princeton senior in the early 60's, I was required to submit a senior thesis in my department, Art and Architecture. Researching and writing the paper took up an entire two semesters, and counted as one course. At the end of my junior year I met with my thesis advisor to discuss my choice of a topic: the noted regionalist painter Thomas Hart Benton (one of the triumvirate that included Edward Hopper and Grant Wood). Benton was a longtime neighbor of my family on Martha's Vineyard, and I knew him, his wife Rita, and daughter Jessie well. I had spent a lot of time in his home and studio, and was intimately acquainted with his ideas about art, his work and working process. I had access to sketches, little known paintings of his, and his work in process.

Benton had at one time been one of the most famous and well-paid artists in the country, the first painter to appear on the cover of Time Magazine (Dec, 24, 1934). By the 50's he had gone out of favor with critics, academics, and collectors, as abstract expressionism came to dominate the art scene. That fact alone would have made for any number of possibilities for a thesis, but when I mentioned Benton to my advisor he practically shouted at me, "No! Absolutely not. Thomas Benton is not an artist, he's an illustrator," his tone dripping with contempt.

I folded, and ultimately wrote about 20th century religious art, a subject that had absolutely no attraction for me. It took me years to realize how unfortunate it was I had lacked the courage to defy my professor and write about Benton anyway. In any case I don't think I could have received a lower grade.

I might conceivably have defended Benton against the charge, one that virtually amounted to cultural heresy, but a more interesting approach would have been to use Benton to defend illustration. What were the Old Masters, after all, if not illustrators? Michelangelo's Sistine Ceiling is illustration on an epic scale. Raphael was an illustrator. Caravaggio, Velasquez, Rubens, and Rembrandt were illustrators, along with just about every known artist of the time. They didn't merely paint pictures, they told stories: bible stories, myths, historical sagas, contemporary events, inventions.

Illustration and narrative exist as one, and thus, unfairly, narrative got a bad name as well in the late 20th century. The idea that a single image could embody more than an instant, but rather suggest a timeline that in effect had no beginning or end, became anathema to those who considered themselves the snarling watchdogs at the gates of culture. No beginning or end, because who, gazing at any one of a number of iterations of, say, Susanna and the Elders, and without previously knowing this age-old tale of lust, human weakness and hypocrisy, as pertinent now as it was five hundred years ago, can say what exactly set in motion the events playing out before us, or how they will resolve?

(Thomas Hart Benton)

Narrative is such a deeply and intrinsically human impulse that it's almost inconceivable that anyone would declare it off-limits in any particular art form, especially at a time when we are inundated with so many film and television manifestations that rely almost exclusively on cliches, tropes, and shopworn plot gimmicks. The instinct for storytelling goes back hundreds of thousands of years, and it can be reasonably argued that it evolved in us as a survival strategy, enabling early homo sapiens and probably earlier human species as well to contemplate their existence and perpetuate the lives of their ancestors. There is compelling evidence that cave artists found ways to incorporate movement in their work to convey a sense of time passing, much as film animators do today.

Sunday, September 28, 2014

The art that interests me serves a purpose beyond simply

being decorative and pleasing to the eye and emotions. There are behavioral

scientists and evolutionary biologists who believe art has no other reason to

exist than to stimulate the pleasure center in our brains and make us happy.

They contend that unlike those human abilities, traits, and urges that evolved

as survival mechanisms, art is non-essential other than to make existence a little

less brutal (as if that in itself weren’t reason for it to have an important

place in our lives). A colorful shower curtain can give us a little jolt of

joy, but I ask more from a work of art; I want to feel, even if only

instinctively, that the artist has communicated something personal and

compelling. A painting of flowers may be pretty, but it’s less meaningful than

a bunch of actual flowers if the artist hasn’t shared a genuine response to the

flowers. What is it about those particular flowers, at that moment in the

artist’s life, that compels the artist to memorialize them? A pretty landscape

has no more significance than a decorative dinner plate if the artist had no

other intention than to produce a pretty landscape. If we’re to honor the evolutionary

purpose of art in human existence, then we must demand it communicate something

about the artists’ unique and immediate experience of this life.

Thursday, September 25, 2014

I'd always thought of the self-portrait as being someone other than me, as if the subject were a character in a drama. The process of painting myself is not one of flattery, as with most commissioned portraits, but rather of discovery, and I like the idea of stepping outside myself to observe myself. Recently, however, I learned of the late photographer Minor White (1908-1976), whose subjects covered a wide range including portraits, but who specialized in photographing objects in tight close-up so that they appeared abstract. White once declared that every photograph he made, no matter the subject matter, was a self-portrait. By this he meant that the act of creating a work of art is an act of revealing oneself. I've been forced to reassess by ideas about the self-portrait.

Saturday, June 08, 2013

The Little Garden That Couldn't

I've attempted numerous times over the years to transform the tiny patch of dirt in front of my house into something resembling a garden. The only thing me and my brown thumb have to show for it is a half-empty bag of fertilizer that has possibly taken root. Oh, well.

Thursday, June 06, 2013

Face, the Facts

It's a mistake to discuss drawing and photography in terms of which is the superior art. On the other hand, there is a fundamental aesthetic difference, and I've never met a photographer who disagreed with me about this. Photography is the record of a single instant, whereas drawing (as well painting) records the relationship between subject and artist over a period of time and therefore incorporates the concept of change.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)